Swedish Submarine Forces

During the visit, we were shown the shipyard halls in Karlskrona, where sections of two A26-class submarines—Blekinge and Skåne—are being built in parallel. According to current plans, these vessels are scheduled for completion between 2027 and 2028, after which they will be delivered to the 1st Submarine Flotilla, which is based near the shipyard.

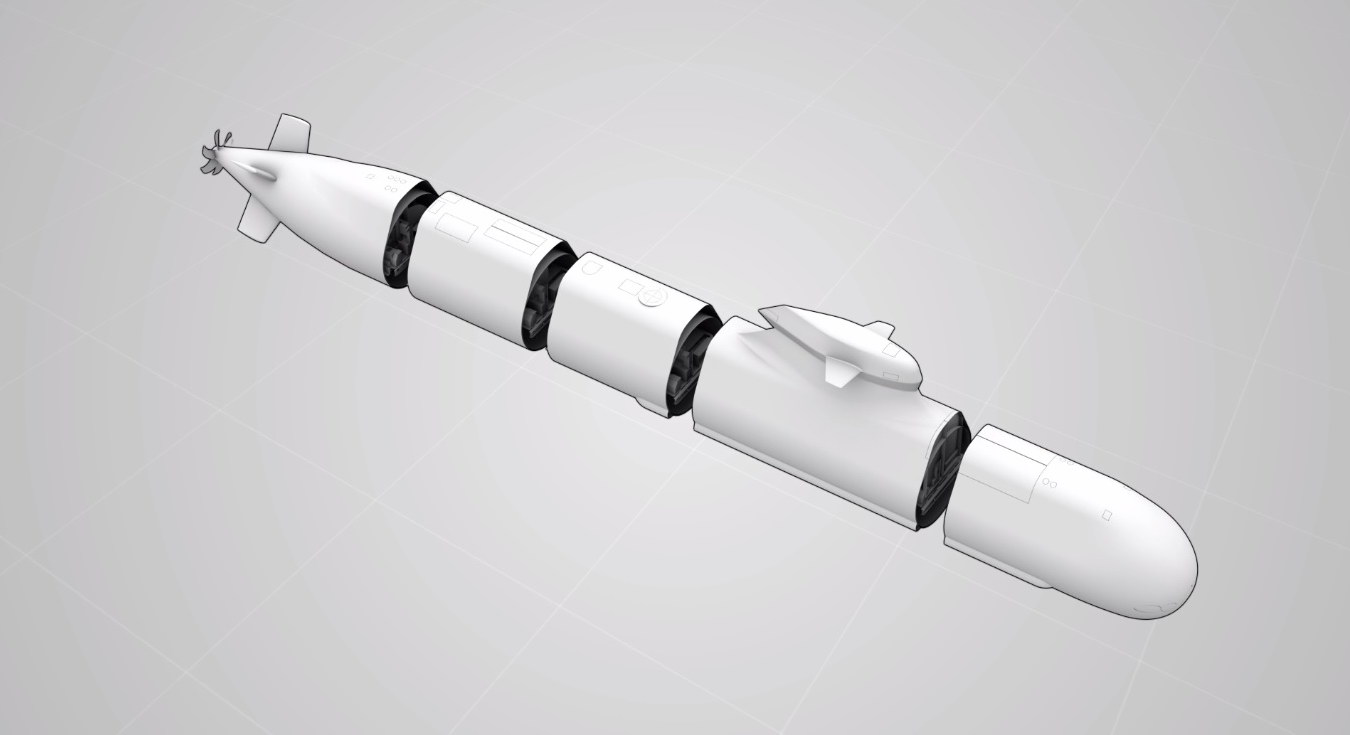

Structurally, the A26 hull is divided into five sections, numbered sequentially from S100 to S500 / Illustration: Saab

Structurally, the A26 hull is divided into five sections, numbered sequentially from S100 to S500 / Illustration: Saab

Currently, the unit operates four submarines: the oldest, HMS Södermanland, belongs to the modernized A17 class (Västergötland, often referred to as the Södermanland class or A17S due to the extent of its upgrades), and three submarines of the A19 (Gotland) class: HMS Gotland, HMS Uppland, and HMS Halland. In addition, the flotilla includes the rescue vessel HMS Belos and the signals intelligence ship HMS Artemis.

Once both A26-class submarines enter service, the oldest submarine, HMS Södermanland, will be decommissioned. At that point, the flotilla will consist of five submarines—an operational strength considered optimal by the Swedish Ministry of Defence. A replacement for Belos, which has been in service for over 30 years (since 1992), is also planned for the first half of the next decade.

In the following decade—the 2040s—Sweden plans to build a new generation of submarines to replace the Gotland-class vessels. According to Saab representatives, work on this future class has already begun. It is worth noting the Swedish philosophy of submarine development: each new class is designed through evolution rather than revolution, building on the proven solutions of its predecessors. This is also the case with the A26, which incorporates many features from the A19. Conversely, during upgrades of the A19 submarines, components developed for the A26 program have been retrofitted back into the older vessels.

Saab emphasizes that the modular design of the A26 allows for customization to meet specific customer requirements, including the insertion of an additional hull section if needed

Saab emphasizes that the modular design of the A26 allows for customization to meet specific customer requirements, including the insertion of an additional hull section if needed

Submarines for the Baltic Sea

Representatives of Saab Kockums emphasized that their submarines are the only ones in the world specifically designed to operate in the unique conditions of the Baltic Sea. They pointed out that the Baltic is an unusual body of water—shallow, with average depths ranging from just 25 to 250 meters (the overall average depth is slightly over 50 meters, with the deepest point—Landsort Deep—reaching 459 meters). These characteristics place particular demands on vessels operating in the region.

As a result, unlike submarines from other countries, Swedish submarines are adapted to safely rest on the seabed. Additionally, because the Baltic is heavily mined—with an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 mines and other unexploded ordnance remaining on the seabed from both World Wars—the Swedish Navy places significant emphasis on designing submarines with high resistance to underwater explosions.

A practical example of this approach can be seen in the previous Gotland-class submarines. During their modernization, the vessels were cut and fitted with an additional hull section / Photo: Saab Kockums / Glenn Pettersson

A practical example of this approach can be seen in the previous Gotland-class submarines. During their modernization, the vessels were cut and fitted with an additional hull section / Photo: Saab Kockums / Glenn Pettersson

For this reason, every new class of submarine introduced into service undergoes live explosive trials—in which a charge simulating a mine explosion is detonated near a submerged vessel. On board are the standard crew along with shipyard personnel, and various measuring devices (including accelerometers) are placed throughout the submarine to record all forces acting on the hull and the extent of deformation caused by the blast. The first such test took place in 1961 on the submarine HMS Hajen, and since 1968, when a similar trial was conducted on HMS Sjöormen, every newly developed submarine class has been subjected to this kind of evaluation. One of them, HMS Näcken, was tested in this way twice: first in 1980 after entering service, and again in 1993 following a major upgrade that included the insertion of an 8-meter hull section housing an air-independent propulsion system with Stirling engines.

Great importance is also placed on minimizing all physical signatures of the submarines, as the shallow waters of the Baltic severely restrict a submarine’s maneuvering space. In such an environment, remaining undetected is crucial. Exceptional care is taken to isolate and silence all onboard systems, and to coat the hull with sound-absorbing material. In the case of the A26, the entire suite of solutions aimed at reducing detectability is encapsulated in the catchy acronym GHOST (Genuine Holistic Stealth).

Blekinge-Class Submarines

Work on a new submarine for the Swedish Navy began in 2005 following the cancellation of the earlier Viking program. That program had envisioned the construction of 10 submarines—two for Sweden and four each for Denmark and Norway. One of the key reasons for Viking’s cancellation was Denmark’s 2004 decision to retire submarines from its navy, which reduced overall demand and made continuation of the project economically unviable.

However, since Sweden still needed a next-generation submarine to replace the Södermanland-class vessels, work began on a new design intended exclusively for its own navy, designated as the A26 class. On February 25, 2010, Kockums signed a contract with the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration (Försvarets materielverk, FMV) to design a next-generation submarine. Tensions began to rise, however, between FMV and Kockums’ then-owner, the German conglomerate ThyssenKrupp, particularly over the division of development costs between Sweden and potential international customers. As a result, at the end of February 2014, FMV cancelled its plans to procure A26 submarines. This decision led to further conflict. A month later, on April 2, the Swedish government officially ended talks with ThyssenKrupp, and on April 8, FMV famously reclaimed all equipment and documentation belonging to the agency from the shipyard.

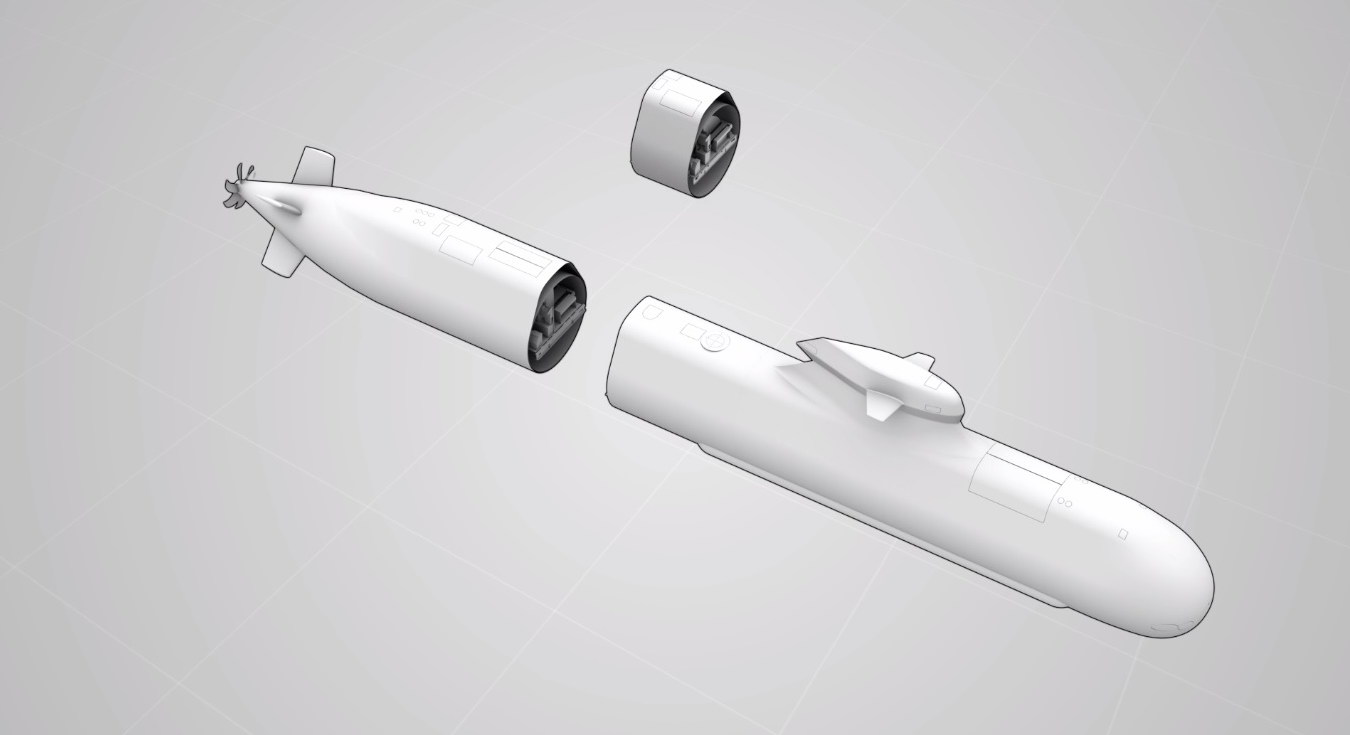

The A26 features an unconventional weapons layout. It is equipped with only four 533 mm torpedo tubes, while the central position in the bow is occupied by the MMP (Multi-Mission Portal)—a large cylindrical lock chamber designed to allow both divers and large unmanned underwater vehicles to exit the submarine / Illustration: Saab

The A26 features an unconventional weapons layout. It is equipped with only four 533 mm torpedo tubes, while the central position in the bow is occupied by the MMP (Multi-Mission Portal)—a large cylindrical lock chamber designed to allow both divers and large unmanned underwater vehicles to exit the submarine / Illustration: Saab

The lack of further prospects for cooperation led the German conglomerate to begin negotiations with Saab regarding the sale of the shipyard (which Saab had already been pursuing in the fall of 2013). These talks concluded with an agreement signed on July 22, 2014. The shipyard, now under the new name Saab Kockums, became part of the Swedish defense group.

Following these developments, the A26 construction program was resumed in early 2015. The contract initially called for both submarines to be delivered by 2022. These deadlines were later pushed back—first to 2024–2025, and then to 2027–2028. The extended timeline was due to delays in development work caused by the slow restoration of production capabilities, modernization of the shipyard after its acquisition from the Germans, and changes in design requirements. One such change was the integration of the new 400 mm Tp 47 torpedoes (also known as SLWT – Saab Lightweight Torpedoes), which entered service in 2022.

On a small and constrained body of water like the Baltic Sea, Sweden places great importance on maintaining continuous underwater operation with minimal need to surface—or even to reach periscope depth. This requires the installation of an additional power source beyond the traditional diesel-electric system: an Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) system. In this case, Sweden has remained committed to the Stirling engine, a thermal engine first adopted for submarines back in the 1980s.

The Stirling engine operates using heat, which is generated by the combustion of diesel fuel in a special chamber. To eliminate dependence on atmospheric oxygen for combustion, the submarine is equipped with liquid oxygen tanks. Compared to competing AIP technologies based on fuel cells, the Stirling engine is significantly less efficient. Its overall efficiency—where thermal energy is first converted to mechanical energy (via piston movement), and then to electrical energy through a generator that powers the electric motor—does not exceed 40%. By contrast, hydrogen fuel cells can reach efficiency levels of 60–80%.

Two A26-class submarines—Blekinge and Skåne—are being built in parallel in the shipyard halls in Karlskrona. According to current plans, they are expected to be completed between 2027 and 2028 / Photos: Saab

Two A26-class submarines—Blekinge and Skåne—are being built in parallel in the shipyard halls in Karlskrona. According to current plans, they are expected to be completed between 2027 and 2028 / Photos: Saab

The Swedish side, however, emphasizes the advantages of its solution, which they believe justify its continued use. The first argument is the simplicity of the design, which allows for maintenance—and even repairs—to be carried out by the crew under operational conditions. A second highlighted benefit is the ease of refueling and oxidizer replenishment. Since the fuel used is standard diesel and the oxidizer is liquid oxygen—both of which are widely available (used in industry and even hospitals)—refueling can be carried out in virtually any port without the need for specialized infrastructure. The refueling process is also relatively quick, taking approximately six hours. In contrast, fuel cell systems require specialized infrastructure, and the potential unavailability of such facilities during wartime operations poses a significant limitation. Additionally, refueling time for fuel cell systems exceeds 24 hours, which increases the risk of attack while the submarine is reestablishing combat readiness.

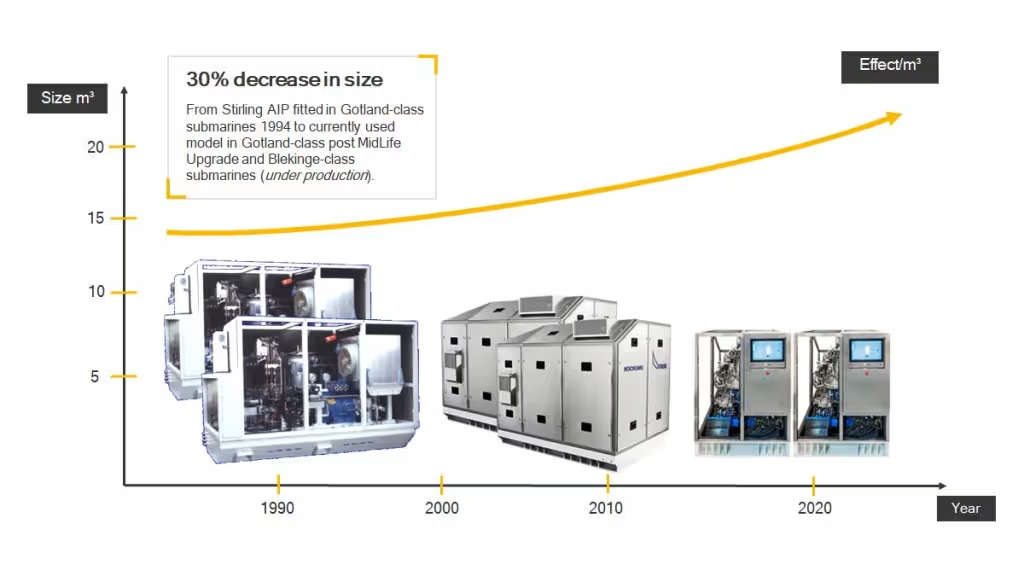

The Swedish AIP (Air Independent Propulsion) system has been under development for 40 years, and it is now in its fourth generation—an improved Mk III variant also installed on the modernized Gotland-class (A19) submarines. The first generation, designated Mk I, was installed on HMS Näcken, which was rebuilt for this purpose starting in 1987. The second generation, considered the first to enter series production—Mk II—was implemented on three Gotland-class submarines. The third generation, Mk III, was introduced in the early 2000s on four modernized Västergötland-class (A17) submarines. Two of these were sold to Singapore as the Archer class, while the remaining two—often referred to as the Södermanland class due to the extent of their upgrades—remained in service with the Swedish Navy.

The current propulsion variant is referred to as an improved Mk III, though the manufacturer classifies it as fourth-generation. While the fundamental operating principle of this type of propulsion remains unchanged, each successive version has focused on improving efficiency and achieving a more compact design. The A26 is equipped with three Stirling engine modules, each generating around 70 kW of power, providing a total of approximately 200 kW, which enables the submarine to maintain a constant submerged speed of around 5–6 knots. At higher speeds, energy consumption exceeds what the AIP system can generate. According to Saab Kockums, their latest submarine can remain submerged for over 18 days while cruising continuously at patrol speed.

However, this type of propulsion is not optimal for all applications. It’s worth noting that the Swedish solution was adopted by Japan for its Sōryū-class submarines. Out of the 12 vessels built, the system was installed only on the first 10 units delivered between 2009 and 2019. The last two, which entered service in 2020 and 2021, no longer featured this propulsion system—instead, they were fitted with lithium-ion batteries. When asked about this, representatives of Saab Kockums explained that the decision reflects the specific operational needs of submarines in oceanic environments. In such settings, greater importance is placed on achieving high submerged speeds and the ability to relocate quickly, rather than simply patrolling at a steady, low speed of a few knots. For this reason, a low-power propulsion system that delivers energy over long periods is less suitable in those conditions. In this context, it was also mentioned that while Saab Kockums is, in principle, ready to integrate lithium-ion battery technology into its submarines, the A26 still uses traditional lead-acid batteries due to safety concerns—specifically the risk of fire associated with lithium-ion cells, which have significantly higher energy density.

What Is the A26 Like?

The A26 is a single-hull submarine measuring 66 meters in length with a displacement of 1,925 tons. Its crew is expected to consist of between 17 and 26 personnel, but due to its potential use for transporting special forces, the vessel can accommodate up to 35 people on board. A strong emphasis has been placed on the submarine’s suitability for unconventional operations, which is reflected in its distinctive weapons and equipment layout. The submarine is equipped with only four 533 mm torpedo tubes—unlike the standard six found on most submarines of this size. Taking the central position in the bow is the MMP (Multi-Mission Portal), a large cylindrical lock chamber designed to allow exit for both divers (e.g., special forces) and large unmanned underwater vehicles, whether remotely operated (ROVs) or autonomous (AUVs). The chamber measures 7 meters in length and 1.5 meters in diameter, and it can hold up to eight divers, allowing them to deploy simultaneously. The area behind the torpedo tubes and the MMP is also modular and can be reconfigured depending on the mission—it can be used to store torpedoes or unmanned underwater vehicles as needed. The A26 is not currently armed with torpedo tube-launched missiles, as the Swedish Navy does not use them. However, according to Saab Kockums, the submarine is designed to be easily adapted to incorporate such systems if requested by a customer.

Structurally, the hull is divided into five sections, numbered sequentially from S100 to S500. The sail (conning tower) is designated S490, and the hull sheathing fore and aft of it is labeled S800.

The Swedes take great care to isolate and silence all onboard equipment from the hull to prevent vibrations from being transmitted to it / Photo: Saab

The Swedes take great care to isolate and silence all onboard equipment from the hull to prevent vibrations from being transmitted to it / Photo: Saab

Numbering begins at the stern, where section S100 houses the main propulsion system—a permanent magnet synchronous electric motor from Schneider, which drives a single propeller via a shaft. The systems supplying power to this motor are located in the next section—S200. This includes, among other things, three 16-liter, 8-cylinder Scania diesel engines housed in separate modules, as well as three modules containing Stirling engines. All these modules are mounted on shock-absorbing platforms designed to isolate equipment from the hull and prevent the transfer of vibrations. This helps minimize the submarine’s acoustic signature and increases the shock resistance of the mounted components in the event of nearby explosions. The next section, S300, contains fuel and oxidizer tanks, along with a rescue lock. Adjacent to it is S400, which houses crew quarters, a galley and mess area, and the command center. Within the control room, on the port side, are the helmsman’s station, propulsion control center, and a dedicated station for special forces command personnel, who may operate from the submarine. On the starboard side, there is a row of multifunction consoles for the Saab 9LV combat management system, used to control all combat operations. The 9LV system integrates data from all of the submarine’s sensors: sonar, as well as electronic intelligence systems—R-ESM (Radar Electronic Support Measures) and C-ESM (Communications Electronic Support Measures). According to Saab, the consoles are standardized and identical to those found aboard Saab’s GlobalEye S106 airborne early warning and surveillance aircraft. It’s worth noting that the A26 is not equipped with traditional periscopes, and therefore none are present in the command center. Instead, modern optronic masts from Sagem are used, each outfitted with up to four different sensors: a daylight camera, thermal imager, laser rangefinder, and more. This setup not only allows visual data to be displayed on any console screen but also enables the system to quickly capture a 360º image and immediately retract the mast. Further analysis of the surface situation can then be conducted using the recorded material—without risking the submarine’s detection.

A26 and Poland’s Next-Generation Submarine

The Swedish submarine is one of the proposals submitted in response to Poland’s Orka program for the acquisition of a new class of submarines. Unfortunately, we did not learn much new on this topic—aside from assurances that Saab Kockums is capable of adapting the design to meet Polish requirements, including the ability to launch missile systems. Naturally, it must be kept in mind that the cost of any design modifications would be borne by the Polish side, although this applies to all competing offers. Without knowing the specific details, it is impossible to determine which option would ultimately be more expensive. Saab also emphasizes that the modular design of the A26 allows for tailoring the submarine to a customer’s specific needs, and that the core costs will largely depend on the additional capabilities requested. When asked about potential delivery timelines for the submarines intended for Poland, we were told only that exact dates are included in the offer but will not be made public.

View of the aft section S100, which houses the main propulsion system—a permanent magnet synchronous electric motor from Schneider that drives a single propeller / Photo: Saab

View of the aft section S100, which houses the main propulsion system—a permanent magnet synchronous electric motor from Schneider that drives a single propeller / Photo: Saab

In the case of the Swedish offer, a favorable factor is the current close and growing defense cooperation between our two countries. Last year, Saab delivered two Saab 340 AEW Erieye airborne early warning aircraft to the Polish Naval Aviation Brigade, and a contract was signed for the delivery of over 6,000 Carl Gustaf M4 shoulder-fired anti-tank grenade launchers. Cooperation is particularly extensive in the maritime domain. Saab supplies Double Eagle SAROV underwater vehicles, which form part of the mine countermeasure systems on Project 258 Kormoran II minehunters, and is currently building two Project 107 Delfin signals intelligence vessels for Poland at the Remontowa Shipbuilding yard in Gdańsk.

Close cooperation in the Baltic region, along with a shared awareness of threats from Russia, provides a strong foundation for future Polish-Swedish collaboration. Whether this will translate into an order for A26 submarines, however, remains uncertain. One concern regarding the A26 is the fact that it is still under construction, and the program has been significantly delayed compared to its original timeline. Furthermore, the lack of missile armament capabilities—at least in the submarine’s current configuration—may be seen as failing to meet Polish requirements (regardless of how justified those requirements may be). This could lead to increased final costs and delays in the construction schedule. Another point of consideration is torpedo armament. Currently, Swedish submarines are equipped exclusively with domestically developed systems—namely, the Tp 62 heavy 533 mm wire-guided torpedoes, which use a combustion propulsion system fueled by hydrogen peroxide and kerosene, as well as electric torpedoes in the unusual 400 mm caliber: the Tp 45 and the newer Tp 47. The latter is part of Saab’s offer to Poland.

The Swedish AIP system has been in development for 40 years and is now in its fourth generation—an improved Mk III variant, also installed on the modernized Gotland-class (A19) submarines / Illustration: Saab

The Swedish AIP system has been in development for 40 years and is now in its fourth generation—an improved Mk III variant, also installed on the modernized Gotland-class (A19) submarines / Illustration: Saab

It should also be noted that financial considerations and the long delivery timeline were major factors that hindered the realization of the interim Orka solution—namely, the concept once announced by Minister Błaszczak of temporarily commissioning one or even both Södermanland-class (A17S) submarines into service.

Which of the offers presented to Poland will prove to be the most favorable will be determined by the procurement process conducted by the Armament Agency, which will ultimately decide who will supply the new submarine for our navy.