The 1919 Decree

The Decree of January 25, 1919, on the Acquisition and Possession of Firearms and Ammunition (published in the Journal of Laws of the Polish State, 1919, No. 9, item 123) was the first legal act of the interwar period concerning firearms. The fact that it was issued just over two months after Poland regained independence suggests that Józef Piłsudski treated the unification of firearm laws in the newly reestablished country as a high priority.

The decree, in Article 1, introduced a general rule stating that the right to acquire, possess, and use any kind of firearm and ammunition was granted only to organizations and civilians who held a permit from the appropriate state authority. This rule was clarified in Article 3 with regard to hunting weapons and short firearms intended for personal protection — such permits were to be issued by the Minister of Internal Affairs or an authorized local authority.

In addition, the decree invalidated all permits issued outside this official process (Article 4) and introduced penalties for violations. Possession of military weapons or materials intended for military use (notably, the decree did not define these terms) could be punished with up to one year in prison or a fine of up to 5,000 marks. Possession of hunting or short firearms without a permit could result in up to three months’ arrest or a fine of up to 3,000 marks (Article 5). Military-grade weapons and materials were also subject to confiscation. Investigations and decisions were handled by administrative authorities.

The 1919 Regulation

On January 29, 1919, Minister of Internal Affairs Stanisław Wojciechowski issued an executive regulation on the possession of firearms and explosives (published in the Journal of Laws of the Polish State, 1919, No. 12, item 133). All civilians and social organizations in possession of firearms without a proper permit were required to surrender them immediately—no later than February 9, 1919—to the district office of the municipal police (Article 1). The authority to issue permits for hunting weapons or short firearms for personal protection was granted to the municipal police, with the approval of the People’s Commissioner (Article 4). Penalties for violating the regulation were to be issued by People’s Commissioners, and appeals to the Minister of Internal Affairs could be made only regarding the amount of the penalty, not the fact that it was imposed (Article 5).

Edmund Rudecki, marksman, loading a sporting rifle equipped with an aperture sight and a support knob for stabilizing the weapon.

The 1920 Regulation

Neither of the two previously mentioned legal acts specified any criteria for issuing firearm permits. This situation remained unchanged until May 31, 1920, when a new executive regulation by the Minister of Internal Affairs, dated May 21, 1920, came into force (published in the Journal of Laws, 1920, No. 43, item 266). From that point on, permits for possessing hunting firearms or handguns were issued by first-instance administrative authorities (Article 1), rather than by the municipal police as before. Hunting firearm permits were issued together with a hunting license. In contrast, when it came to handguns for personal protection, the only official criterion was a “case of compelling necessity” This can hardly be considered a concrete legal standard. The phrase “case of compelling necessity” was extremely vague, and whether or not a permit was granted largely depended on the discretion (or whim) of the official in charge.

The 1921 Council of Ministers Regulation

By the Regulation of the Council of Ministers dated August 5, 1921, concerning the extension of the legal force of the 1919 decree (published in the Journal of Laws, 1921, No. 71, item 472), the decree was made applicable to the Nowogródek, Polesie, and Volhynia voivodeships, as well as to the counties of Grodno, Białowieża, and Wołkowysk in the Białystok voivodeship. This was the last regulation issued by a central state authority related to the Chief of State’s decree.

The 1921 Treaty of Riga – a treaty between Poland, Soviet Russia, and Soviet Ukraine that ended the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1920 and, among other things, established Poland’s eastern border.

National shooting and archery competition of the Polish Scouting Association in Poznań. Pistol shooting at the shooting range on Bukowska Street.

Government Circulars (1921–1925)

Further executive regulations were issued by the Minister of Internal Affairs in the form of government circulars. These circulars covered, among other things, the design of firearm permit forms (1921), firearm possession by diplomats (1922), permits for the trade of hunting weapons (1923), and the acquisition of firearms and ammunition by military personnel and state police officers (1924). In 1925, the requirement for a permit was extended to include sporting firearms of 6 mm caliber using rimfire ammunition. The large number of executive acts related to the 1919 decree stemmed from the need to adapt regulations to the diverse legal systems that had previously existed in the territories of the former partitions. Not all of these regulations were uniformly applicable across the entire country. Furthermore, the 1919 decree consisted of only seven articles, and the implementing regulations were even shorter — which made further elaboration and clarification necessary.

The 1932 Presidential Decree

On January 1, 1933, the Presidential Decree titled “The Law on Firearms, Ammunition, and Explosive Materials”, issued on October 27, 1932, came into force. This marked the final stage in the long process of unifying firearm legislation in post-partition Poland. This act, issued by President of the Republic of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki, was a regulation with the force of law (Journal of Laws, 1932, No. 94, item 807), adopted in accordance with the March Constitution of 1921, later amended by the so-called August Novelization of 1926

One of the most striking features of the decree is the glossary included in Article 1. It introduced a very broad definition of “weapon” — as any tool intended to cause bodily injury, directly or indirectly (Art. 1, Sec. 1). Interestingly, however, the regulation did not cover bladed weapons (Art. 3). Ammunition was defined as ready-to-use cartridges and projectiles for firearms, including all types of explosive projectiles (Art. 1, Sec. 2). For the first time, the now-controversial term “essential parts of a firearm” appeared, a phrase that would be repeated in many later legal acts, including in the current law still in force today. Specifically, it stated that ready-made or processed essential parts of firearms or ammunition are to be considered firearms or ammunition. However, these parts were not defined in the act itself, with that responsibility deferred to a separate executive regulation (Art. 1, Sec. 3).

The topic of “essential parts” also appears in Article 14. It stipulated that only firearms bearing a manufacturer’s name or trademark, a serial number, and — in the case of firearms — proof marks confirming durability and safety could be distributed. These restrictions were introduced largely due to the proliferation of illegal workshops producing low-quality, unsafe weapons that frequently caused accidents. While the problem of weapons entering the criminal underworld was also a concern, the regulation’s primary focus was clearly public safety.

The regulation maintained the principle that firearms could be acquired, possessed, or carried for personal use only with a valid permit issued by the authorities (Art. 18, Sec. 1). Notably, Article 44, Section 1 of the regulation stated that a future regulation by the Minister of Internal Affairs would lay down detailed safety requirements for the construction and operation of shooting ranges used for firearms training, as well as rules for storing, handling, and using firearms at such facilities.

The 1933 Executive Regulation

In the executive regulation issued by the Minister of Internal Affairs on March 23, 1933, concerning firearm permits for personal use and the acquisition and disposal of such weapons (Journal of Laws, 1933, No. 22, item 179), several exceptions were outlined for which no permit was required. These included: all types of firearms manufactured before 1850, air rifles with a caliber of no more than 6 mm, automatic devices used solely to secure access to buildings or rooms from unauthorized entry, and devices used exclusively for the slaughter of horses and livestock (§23 of the regulation).

Article 19, section 1 of the regulation stated that permits were to be issued at the discretion of powiat (county-level) general administrative authorities, and granted to individuals regarding whom there was no concern that the firearm would be used in a way contrary to the interests of the State or to public safety, peace, or order. This broad discretionary power was limited only by a set of negative criteria. Permits could not be granted to: minors under the age of 17 (although minors aged 14 and up could receive a permit for sporting or hunting purposes upon request by a parent or guardian), individuals who were mentally ill, habitual drunkards or drug addicts, vagrants, or anyone who had been convicted twice for violating the same provision of the regulation on firearm acquisition, possession, or carrying, if less than three years had passed since the last conviction (Art. 20). Most importantly, although the process for issuing permits was entirely discretionary, the regulation did not impose any requirement to justify the purpose or “need” for owning a firearm.

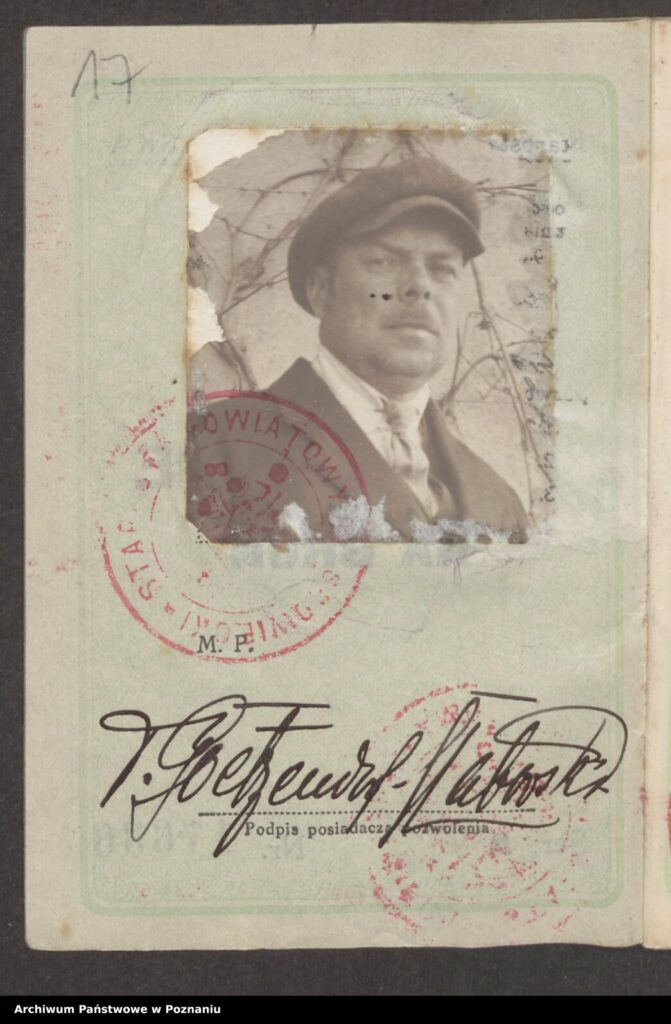

Permits

Three types of firearm permits were provided for in Article 22 of the regulation and §§1–4 of the executive regulation:

- Permit for possession – granting the right to possess the specified firearm(s) within the holder’s residence or another designated location.

- Permit for possession and carrying – allowing the holder to possess and carry the firearm anywhere not prohibited by law (it was noted that transporting such firearms on public transport was permitted only if unloaded).

- Permit for maintaining a collection of firearms for museum, scientific, or commemorative purposes – granting only the right to possess and store firearms in designated premises listed in the permit.

The “private” possession permits were issued for a maximum of three years, with the possibility of renewal for subsequent periods of up to three years. Collection permits, on the other hand, could be issued indefinitely (§7 of the executive regulation).

A permit could be revoked at any time if the county-level general administrative authority considered it necessary in the interest of the State, or for reasons of public safety, peace, or order. Revocation was mandatory, however, if it was discovered that the permit holder belonged to any of the categories listed in Article 20 (i.e., the disqualifying conditions described earlier). Interestingly, if a delay on the part of the county authority posed a danger, any other administrative authority was allowed to temporarily confiscate the firearm permit, provided the county authority was immediately notified, which was then obligated to issue a formal decision (Art. 24, Sections 1 and 2).

The 1939 Regulation

The term “essential parts of firearms and ammunition” was finally defined in the Regulation of the Minister of Internal Affairs dated April 26, 1939 (Journal of Laws, 1939, No. 41, item 273), issued in consultation with the Ministers of Military Affairs and Industry and Trade, concerning essential parts of firearms and ammunition.

Under this regulation, essential parts of firearms were defined as the barrel and any parts that close the rear of the barrel during firing or form an extension of the barrel (such as the bolt or the cylinder of a revolver). In the case of ammunition, the projectile and the cartridge case were considered essential parts.

Summary

The Presidential Decree of 1932, as a comprehensive legal act regulating access to firearms, remained in force — despite changing socio-political conditions — for nearly 30 years, until 1961, when the Act of January 31, 1961 on Firearms, Ammunition, and Explosive Materials (Journal of Laws, 1961, No. 6, item 43) came into effect.

In summary, an analysis of the legal regulations in force during the Second Polish Republic reveals that public administration authorities had virtually complete discretion in issuing firearm permits. Unfortunately, statistical data on how many permits were granted during the interwar period is difficult to obtain. This naturally raises further questions: How many Poles actually owned firearms? Did the authorities abuse this discretion to the detriment of ordinary citizens? Was having personal connections helpful, or even essential, to obtaining a permit?

And finally — Is it really true that firearms were only taken away from Polish citizens by the communists during the People’s Republic of Poland?

Adam Koper is a legal advisor and the founder of KOPER Legal Office (KOPER Kancelaria Prawna).

Photo credit: National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe)

P: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

Bibliography:

Kasprzak, J., Brywczyński, W. Nielegalne posiadanie broni i amunicji. Studium prawo-kryminalistyczne. Białystok 2013.

Wójcikiewicz, J. Posiadanie broni palnej przez obywateli. Instytut Spraw Publicznych, Warszawa–Kraków 1999.

This article was originally published in MILMAG, issue 02/2018.