Solar Orbiter, an ESA-led mission with strong NASA participation, will provide the first views of the Sun’s uncharted polar regions, giving unprecedented insight into how our parent star works.

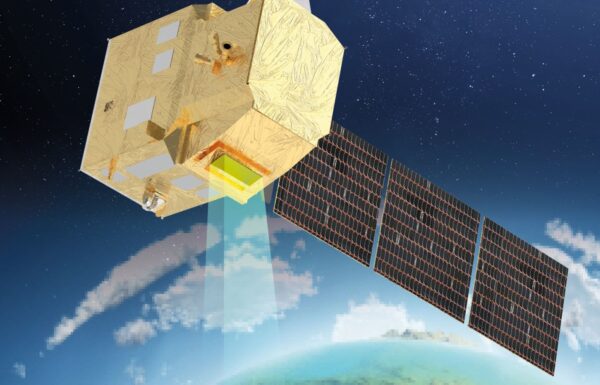

ESA’s Solar Orbiter mission lifted off on an Atlas V 411 from Cape Canaveral, Florida on 10 February on its mission to study the Sun from new perspectives / Picture: ESA

It will also investigate how intense radiation and energetic particles being blasted out from the Sun and carried by the solar wind through the Solar System impact our home planet, to better understand and predict periods of stormy ‘space weather’. Solar storms have the potential to knock out power grids, disrupt air traffic and telecommunications, and endanger space-walking astronauts, for example.

‘As humans, we have always been familiar with the importance of the Sun to life on Earth, observing it and investigating how it works in detail, but we have also long known it has the potential to disrupt everyday life should we be in the firing line of a powerful solar storm’, said Günther Hasinger, ESA Director of Science.

‘By the end of our Solar Orbiter mission, we will know more about the hidden force responsible for the Sun’s changing behaviour and its influence on our home planet than ever before’, he added.

‘Solar Orbiter is going to do amazing things. Combined with the other recently launched NASA missions to study the Sun, we are gaining unprecedented new knowledge about our star’, said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for Science at the agency’s headquarters in Washington.

‘Together with our European partners, we’re entering a new era of heliophysics that will transform the study of the Sun and help make astronauts safer as they travel on Artemis program missions to the Moon’, he added.

At its closest, Solar Orbiter will face the Sun from within the orbit of Mercury, approximately 42 million kilometres from the solar surface. Cutting-edge heatshield technology will ensure the spacecraft’s scientific instruments are protected as the heatshield will endure temperatures of up to 500ºC – up to 13 times the heat experienced by satellites in Earth orbit.

‘After some twenty years since inception, six years of construction, and more than a year of testing, together with our industrial partners we have established new high-temperature technologies and completed the challenge of building a spacecraft that is ready to face the Sun and study it up close’, adds César García Marirrodriga, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project manager.

Solar Orbiter will take just under two years to reach its initial operational orbit, making use of gravity-assist flybys of Earth and Venus to enter a highly elliptical orbit around the Sun. The spacecraft will use the gravity of Venus to slingshot itself out of the ecliptic plane of the Solar System, which is home to the planetary orbits, and raise its orbit’s inclination to give us new views of the uncharted polar regions of our parent star.

The poles are out of view from Earth and to other spacecraft but scientists think they are key to understanding the Sun’s activity. Over the course of its planned five-year mission, Solar Orbiter will reach an inclination of 17º above and below the solar equator. The proposed extended mission would see it reach up to 33º inclination.

Solar Orbiter will use a combination of 10 in situ and remote-sensing instruments to observe the turbulent solar surface, the Sun’s hot outer atmosphere and changes in the solar wind. Remote-sensing payloads will perform high-resolution imaging of the Sun’s atmosphere – the corona – as well as the solar disc. In situ instruments will measure the solar wind and the solar magnetic field in the vicinity of the orbiter.

Based on a press release from ESA